“The sweetest honey is loathsome in its own deliciousness. And in the taste destroys the appetite.”

Let’s be clear: English has a funny relationship with knowledge and knowledge retrieval. Pick any two English textbooks and you’ll see what I mean. They are never alike. They don’t have the same topics, terminology or even approaches to the subject. The knowledge taught will be vastly different. That’s why schools rarely teach English through textbooks. We cherry pick aspects because the rest of the book doesn’t do it how we see fit.

Look at how Knowledge Organisers were used by English departments, when they were all the rage. They focused on plot, key characters and some contextual background. They were useful to ensure that everybody knew the plot, but I’d argue you aren’t teaching the text properly if the students can’t recall the plot or the key characters. That is the beauty of narratives. They are instantly stored in memory. I can remember films I watched decades ago. The same applies to books. Our brains are stored for retaining narratives. It is just the rest of it that is the problem. My Year 11 can recall the plot of ‘Romeo and Juliet’. Mostly the rude bits and the death scenes. But, nonetheless, they can remember it. What they lack, like most students, is the knowledge of subtle aspects in the play such as the writer’s intent, the audience’s reaction to certain moments, less dramatic moments, characters with only one line, and the reasons behind choices. Yet, we boil knowledge in English to quotations. If they can remember quotations from the text, they can write well.

Now, the knowledge monster has developed a new head: knowledge retrieval at the start of a lesson. Across the land, leaders are insisting that lessons start, including English, with some knowledge retrieval. English teachers across the land are responding with comments akin to Harry Enfield’s ‘Kevin the Teenager’: WHAT? THIS IS SO UNFAIR! English doesn’t lead itself naturally to knowledge retrieval. Mainly, because we pull on lots of knowledge domains that don’t actually appear in English curriculums. I’d use a student's understanding of fishing to explore a poem. I’d use a student’s knowledge of plants to understand what an image means in a play. I’d use a student’s knowledge of Brighton when reading a piece of nonfiction. We don’t read texts in isolation. We knit threads, connections and webs between things. If we taught things in isolation, then my SOW for Romeo and Juliet might run something like this:

Lesson 1 - Learn about Italy.

Lesson 2 - Learn about Verona.

Lesson 3 - Learn about the culture of Italy.

Lesson 4 - Learn about England's attitude towards Italy in Elizabethan times.

We don’t work that way. Texts don’t work in neat, pretty ways. They work like spider webs. They sit in the middle and we look at how they connect. We work from the centre to the outside. Not from the outside to the middle, which is what other subjects do. To know A, we need to cover X,Y and Z. Instead it is messy.

The other problem with English is the transient nature of the things we teach. Yes, we teach novels, but that isn’t really ‘powerful knowledge’ (copyright Ofsted). The knowledge of Long John Silver having one leg is of limited value. It’s of use when studying the novel in Year 7, but will they be able to use that knowledge when looking at another text in Year 8? Not really. That knowledge does not have longevity as it is only needed for that text. It ‘might’ be of use if there is direct reference to the character in another book. This is what makes knowledge retrieval problematic in English. Yes, I could make some knowledge retrieval questions at the start of a lesson on the text we are studying, but it serves very little value in the wider picture of learning.

Everybody loves terminology and it seems that knowledge has got its own set of words around knowledge. The problem is that these only over complicate things. For me, there are three areas of knowledge in English - knowledge / skills / experience. Now, I think it is important that we see English in three areas. The webby nature of it means that everything is connected, but they can stand on their own occasionally. The ‘knowledge’ is a large part. That might be the knowledge of what a simile is and what not a simile is. The ‘skill’ is the ability to replicate a simile in their own writing, which will demonstrate their knowledge but also their ability to manipulate it. The ‘experience’ is the area that is always missing, I think. That is the experience of seeing multiple examples in various contexts. The ‘experience’ is the key element of this triangle, which I think has been missing for a long time from discussions. Everything has been clumped together and ‘experience’ has been neglected.

English is largely about experience. We give students multiple experiences - novels, plays, similes, images, sentences, words used in different contexts - and this is what makes the subject so rich and beautiful. We are about the experience and the danger with emphasis on knowledge is that it neglects skill and experience. The reading of ‘Treasure Island’ is an experience that I want students to use when faced with another text. There may be something small that resonates, echoes or contrasts with ‘Great Expectation’ in Year 8. I don’t want them to recall everything about the plot, characters or quotations for retesting in following years because it doesn’t have that much value. The knowledge of the experience is the important thing. That knowledge isn’t testable. You cannot test it. It is an experience. Part of that experience is building knowledge, but it is a snowball effect rather than a discrete thing that can be tested and retested.

Our relationship with knowledge needs to be reasserted for English. Yes, do knowledge retrieval at the start of the lesson, but it needs to be integrated into the skill or experience elements within English. We don’t just do knowledge; we do other things that are reliant on some form of knowledge. The retrieval should be about building webs or connections and not reliant on spurious knowledge that isn’t connected. I think that there are some people who think that everything has become about knowledge in English and I don’t think that is the case. It is a part of the lesson but it doesn’t dominate the lesson - and that’s what we need to be mindful of. The sweetest honey is loathsome in its own deliciousness. We need to work on building a healthy relationship around knowledge and developing an appropriate balance. Other subjects can bathe in knowledge, but we in English sprinkle it around like holy water. It is part of the ceremony, but we use it sparingly, because it is blessed.

We’ve been using Carousel to help with our knowledge retrieval in English and in particular KS3. The great thing about the Carousel system is it allows for a lot of freedom from an English teaching perspective. Unlike other systems, it allows for students to write free text, which means that multiple interpretations can be accepted or explored. There’s no expectation that English has to fit down a simplistic binary ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ route. In responding, students can provide different examples and they can be assessed as correct. English is a subject where there are several right answers and not simply one.

Plus, as with the new questions for GCSE Literature texts they have released, there is scope to work on the ‘webbiness’ of knowledge in English. The questions are not simply about recalling answers parrot fashion, but about connecting parts of texts with each other or effect with techniques. A lethal mutation I have seen with knowledge retrieval in English is a complete focus on quotations to the point that students are reciting quotations and just that. English is the subject of thinking and not recalling. If we make all the knowledge about quotations, then we are not arming them to think. Most GCSE essays need ‘several’ quotations or references to the text. Only ‘several’. If we make knowledge retrieval just about quotations, we are just filling up buckets. We need to make knowledge retrieval around quotations draw attention to the webbed nature of English, as Carousel has done with their questions. See more about Carousel here.

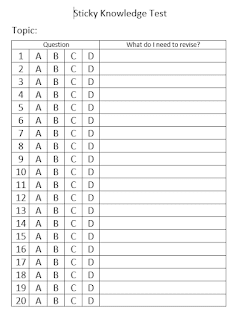

As a school, we’ve been looking at how we can use Carousel in other ways. So, for each year group, we have a bundle of questions related to the powerful knowledge taught in previous years and that year so that we can revisit, revise, and connect different bits of knowledge together. When visiting Macbeth in Year 8, we can use the questions from Year 7 on Shakespeare’s theatre as part of our knowledge retrieval. We have even used it for the knowledge around exam papers. See below.

But, on a day-to-day basis, you don’t always want to have clear knowledge questions. You might want to have skills or experience based questioning. That’s why we have played around with knowledge retrieval. Are there things that I can do with knowledge retrieval that is less so much about the knowledge aspect and more about the skill or the experience?

Retrieval around word meaning

We have a bank of words and we can start with students defining the words. Students are then primed for doing this on a text they haven’t read before. Gets them thinking about word meaning from the start. Or, they look at creating a sentence based on these words. Or, if you are studying a text, see if they can use them to describe aspects of the text.

Retrieval around syllables

We’ve placed emphasis on students’ knowledge of syllables, alongside work on phonemes too, so we have a bank of words. Students are testing their knowledge of what a syllable is, but also working on the skill to identify the syllables in a word. Yes, I could have created questions around ‘what is a syllable?’ but that doesn’t address the ‘webbiness’ of English. Here we prime students so they can look at rhythm in a line of poetry or a line from Shakespeare. Or, their own poetry writing. We also mix it up with knowledge around stressed and unstressed syllables.

Retrieval around techniques

Students never need to repeat a definition of a simile, metaphor or personification in their writing for English, yet we constantly ask them to define them. Here, we present examples for students to identify. They have a one in three chances of getting it right, but it helps us to understand if they know the concept. It provides them with the experience of others but also a starting point for writing their own. Which one is best? Which could you easily improve? Which one could you expand on? Which one could you add more to the sentence? We are testing their knowledge retrieval but we are working on their skills and experience at the same time.

Knowledge retrieval isn’t that hard to do, but it can become meaningless if it isn’t done with thought or understanding. It is so easy to write questions about defining techniques or filling the blanks of quotations, but will it improve their English skills? No. I have known hundreds of students who could give me a crystal clear definition of a simile, yet their own similes in their writing are rubbish. If we focus too much on the knowledge, we miss out on the skill and the experience part of the subject. Where is your skill retrieval in the lesson? Where is your experience retrieval in the lesson? Knowledge connects, but it is like a web in our subject. You cannot focus on it alone. There is room for all three parts - knowledge, skills, experience - and English teachers need to ensure there is a balance between all three.

English teachers are the spiders of the knowledge world. We spin our webs all over the place and we wait for some unsuspecting creature to become ensnared in the web. We listen for the vibrations on a thread. We knit connections where are none.

Thanks for reading,

Xris